Motivation

Lately I have been thinking about one of the most exciting concepts for me to teach in a programming course: how to write functions. Functions have syntactical, technical, and aestetic qualities that all have to align to create a “good” function. The R for Data Science book has a great chapter that touches on many of these issues, including the problem of how to make good names for arguments. Naming things is a notoriously hard problem in programming, and this chapter has a subsection about how to pick both aesthetically good names and names that conform to the argument names in other families of functions in R.

R has several package ecosystems that often have their own conventions, so this got me thinknig: how could you disocver what arguments are commonly used in a family of packages so that you could use the same argument names in your own functions? Conceptually this should be a simple enough task since R has so many features for computing on the langauge which one of my favorite things to do!

So first we will grab all of the functions in a package, and then we can extract

the argument names for each function. After some searching I found the

lsf.str() function which is new to me, but will give us every function in a

package. Let’s test it out with the relatively small postcards package.

library(postcards)

lsf.str("package:postcards")## create_postcard : function (file = "index.Rmd", template = "jolla", create_dir = FALSE, edit = TRUE,

## create_image = TRUE)

## jolla : function (css = NULL, includes = NULL)

## jolla_blue : function (css = NULL, includes = NULL)

## onofre : function (css = NULL, includes = NULL)

## trestles : function (css = NULL, includes = NULL)The syntax for package names with lsf.str() is package:[name of package]

which I don’t really understand, but it works! Also notice that the postcards

package has to be loaded for lsf.str() to work. Now that we have all of the

functions in this package we can get all of the arguments with args().

library(tidyverse)

lsf.str("package:postcards") %>%

as.character() %>%

map(compose(args, as.list, names, ~ keep(.x, nzchar), .dir = "forward"))## [[1]]

## [1] "file" "template" "create_dir" "edit" "create_image"

##

## [[2]]

## [1] "css" "includes"

##

## [[3]]

## [1] "css" "includes"

##

## [[4]]

## [1] "css" "includes"

##

## [[5]]

## [1] "css" "includes"It’s working nicely, but this is R after all, so wouldn’t it be better to have this information in a data frame?

tibble(Package = "package:postcards") %>%

mutate(Function = list(lsf.str(Package))) %>%

unnest(Function) %>%

mutate(Function = as.character(Function)) %>%

mutate(Arg = map(Function,

compose(args, as.list, names, ~ keep(.x, nzchar), .dir = "forward")

)) %>%

unnest(Arg, keep_empty = TRUE)## # A tibble: 13 x 3

## Package Function Arg

## <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 package:postcards create_postcard file

## 2 package:postcards create_postcard template

## 3 package:postcards create_postcard create_dir

## 4 package:postcards create_postcard edit

## 5 package:postcards create_postcard create_image

## 6 package:postcards jolla css

## 7 package:postcards jolla includes

## 8 package:postcards jolla_blue css

## 9 package:postcards jolla_blue includes

## 10 package:postcards onofre css

## 11 package:postcards onofre includes

## 12 package:postcards trestles css

## 13 package:postcards trestles includesLarger Packages

Now that we can get this information into a tidy data frame, we can do some

exploratory data analysis. Let’s look at a much bigger and more popular set of

functions like the base package.

fn_tbl_base <- tibble(Package = "package:base") %>%

mutate(Function = list(lsf.str(Package))) %>%

unnest(Function) %>%

mutate(Function = as.character(Function)) %>%

mutate(Arg = map(Function,

compose(args, as.list, names, ~ keep(.x, nzchar), .dir = "forward")

)) %>%

unnest(Arg, keep_empty = TRUE)

fn_tbl_base## # A tibble: 3,190 x 3

## Package Function Arg

## <chr> <chr> <chr>

## 1 package:base - e1

## 2 package:base - e2

## 3 package:base -.Date e1

## 4 package:base -.Date e2

## 5 package:base -.POSIXt e1

## 6 package:base -.POSIXt e2

## 7 package:base : <NA>

## 8 package:base :: pkg

## 9 package:base :: name

## 10 package:base ::: pkg

## # … with 3,180 more rowsAt the top of this data frame we can see several operators and their arguments.

It appears that : does not have any arguments, which is certainly not

intuitive. Let’s look at all of the functions that don’t have arguments in

base:

fn_tbl_base %>%

filter(is.na(Arg)) %>%

pull(Function)## [1] ":" "("

## [3] "[" "[["

## [5] "[[<-" "[<-"

## [7] "{" "@"

## [9] "@<-" "&&"

## [11] "<-" "<<-"

## [13] "=" "||"

## [15] "~" "$"

## [17] "$<-" "baseenv"

## [19] "break" "closeAllConnections"

## [21] "contributors" "Cstack_info"

## [23] "date" "default.stringsAsFactors"

## [25] "emptyenv" "extSoftVersion"

## [27] "for" "function"

## [29] "getAllConnections" "geterrmessage"

## [31] "getLoadedDLLs" "getRversion"

## [33] "getTaskCallbackNames" "getwd"

## [35] "globalenv" "iconvlist"

## [37] "if" "interactive"

## [39] "is.R" "l10n_info"

## [41] "La_library" "La_version"

## [43] "libcurlVersion" "licence"

## [45] "license" "loadedNamespaces"

## [47] "loadingNamespaceInfo" "memory.profile"

## [49] "nargs" "next"

## [51] "nullfile" "pcre_config"

## [53] "proc.time" "R.Version"

## [55] "repeat" "return"

## [57] "search" "searchpaths"

## [59] "stderr" "stdin"

## [61] "stdout" "sys.calls"

## [63] "Sys.Date" "sys.frames"

## [65] "Sys.getpid" "Sys.info"

## [67] "Sys.localeconv" "sys.nframe"

## [69] "sys.on.exit" "sys.parents"

## [71] "sys.status" "Sys.time"

## [73] "while"We can see that there are several operators that supposedly don’t have any

arguments, plus special words in R like function, if, break, and return.

There are also some classics in this list like getwd() and a personal favorite

of mine: is.R().

Individual Arguments

To get back on task, let’s look at the most common arguments in base, assuming

I want to write my own functions that integrate well with the base package:

fn_tbl_base %>%

count(Arg, sort = TRUE)## # A tibble: 586 x 2

## Arg n

## <chr> <int>

## 1 x 621

## 2 ... 443

## 3 <NA> 73

## 4 value 62

## 5 object 31

## 6 expr 29

## 7 con 28

## 8 e1 28

## 9 e2 28

## 10 na.rm 28

## # … with 576 more rowsIt looks like x is by far the most popular argument in base followed by

.... Off the top of my head I can think of a few functions where x is the

first argument, I wonder if that is generally the case?

fn_tbl_base %>%

group_by(Function) %>%

mutate(Order = 1:n()) %>%

filter(Arg == "x") %>%

pull(Order) %>%

table()## .

## 1 2 3

## 606 12 3Wow x is almost always the first argument whenever it is used! Let’s take a

look at the exceptions:

fn_tbl_base %>%

group_by(Function) %>%

mutate(Order = 1:n()) %>%

filter(Arg == "x") %>%

filter(Order != 1)## # A tibble: 15 x 4

## # Groups: Function [15]

## Package Function Arg Order

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <int>

## 1 package:base agrep x 2

## 2 package:base agrepl x 2

## 3 package:base atan2 x 2

## 4 package:base backsolve x 2

## 5 package:base chartr x 3

## 6 package:base Filter x 2

## 7 package:base Find x 2

## 8 package:base forwardsolve x 2

## 9 package:base grep x 2

## 10 package:base grepl x 2

## 11 package:base grepRaw x 2

## 12 package:base gsub x 3

## 13 package:base Position x 2

## 14 package:base Reduce x 2

## 15 package:base sub x 3Looks like most of these functions are in the grep family or they have to do

with functional programming. Also I never knew about chartr(), that looks like

it could be useful in the future.

Comparing Numbers of Arguments Between Packages

Beyond just looking at argument names, we might also be concerned about how many

arguments are in our functions. Is it gauche to have too many arguments? Let’s

take a look in base again:

fn_tbl_base_n_args <- fn_tbl_base %>%

group_by(Function) %>%

mutate(Count = n()) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(Count = map2_int(Arg, Count, ~ if_else(is.na(.x), 0L, .y))) %>%

select(-Arg) %>%

unique()

fn_tbl_base_n_args %>%

pull(Count) %>%

summary()## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.000 1.000 2.000 2.528 3.000 22.000fn_tbl_base_n_args %>%

pull(Count) %>%

hist(breaks = 20, main = "Number of Arguments Per Function in base",

xlab = "Number of Arguments")

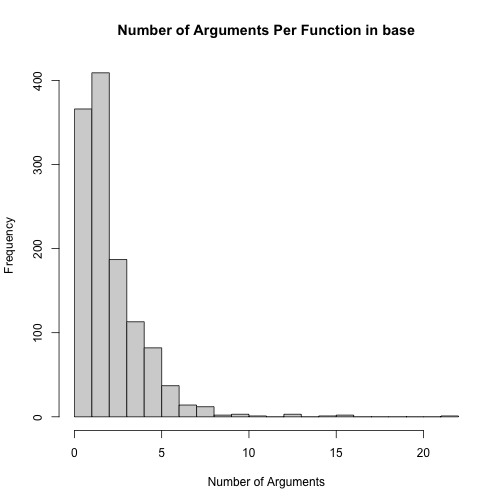

It looks like most functions in base don’t have many arguments. Let’s look at

ggplot2, a very popular package that I know has several functions that use

many arguments.

library(ggplot2)

fn_tbl_ggp2 <- tibble(Package = "package:ggplot2") %>%

mutate(Function = list(lsf.str(Package))) %>%

unnest(Function) %>%

mutate(Function = as.character(Function)) %>%

mutate(Arg = map(Function,

compose(args, as.list, names, ~ keep(.x, nzchar), .dir = "forward")

)) %>%

unnest(Arg, keep_empty = TRUE)

fn_tbl_ggp2_n_args <- fn_tbl_ggp2 %>%

group_by(Function) %>%

mutate(Count = n()) %>%

ungroup() %>%

mutate(Count = map2_int(Arg, Count, ~ if_else(is.na(.x), 0L, .y))) %>%

select(-Arg) %>%

unique()Let’s see which functions have the most arguments:

fn_tbl_ggp2_n_args %>%

arrange(desc(Count))## # A tibble: 405 x 3

## Package Function Count

## <chr> <chr> <int>

## 1 package:ggplot2 theme 95

## 2 package:ggplot2 guide_colorbar 28

## 3 package:ggplot2 guide_colourbar 28

## 4 package:ggplot2 guide_bins 23

## 5 package:ggplot2 guide_legend 21

## 6 package:ggplot2 stat_summary_bin 20

## 7 package:ggplot2 binned_scale 19

## 8 package:ggplot2 geom_boxplot 19

## 9 package:ggplot2 geom_dotplot 19

## 10 package:ggplot2 continuous_scale 17

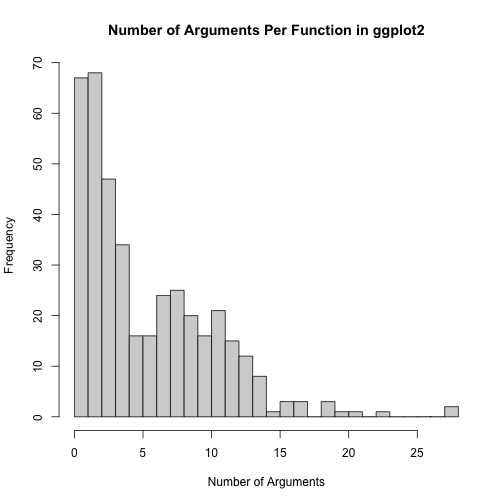

## # … with 395 more rowsWhoa theme() has 95 arguments! I am going to exclude it since it is such an

outlier.

fn_tbl_ggp2_n_args %>%

pull(Count) %>%

discard(~ .x >= 95) %>%

summary()## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.000 2.000 4.000 5.757 9.000 28.000fn_tbl_ggp2_n_args %>%

pull(Count) %>%

discard(~ .x >= 95) %>%

hist(breaks = 20, main = "Number of Arguments Per Function in ggplot2",

xlab = "Number of Arguments")

As we can see here, if you were writing functions to extend ggplot2 you could

get away with including lots of arguments without your users thinking that the

number of arguments was too unusual.

Conclusion

Like many of my posts, this is a proof-of-concept that this kind of thing could be done. If this inspires you to look at or to write packages differently please let me know! In general I am very interested in having more conversations about how to create best practices for writing functions, especially for people developing data science packages.